Revangelion: Part 11 – In the Cruel Still Darkness

If there’s one thing to be said about Evangelion, it’s that the series has no problem reducing mecha on monster action to a genuine side show. In doing so, it elevates personal relationships to the forefront in a fashion befitting a soap opera. I say this as someone who unreservedly loves Attack on Titan, and fully admits that much of its appeal is built on the kind of over-the-top drama befitting daytime television.

Unlike AoT, Evangelion’s characters are so utterly despicable under close scrutiny, or at the very least they are so weird as to be unsympathetic, that the writing can become alienating. I think the only thing that keeps someone coming back to Evangelion is unwavering zeal for reading so deeply into the story that they are effectively writing fan fiction in lieu of finding meaning. And at that point, what is the purpose of this soap opera other getting the audience to do the work of suffering on behalf of the story?

[Retrospective note: Hello, my son. You’ve finally come to terms with it, haven’t you? You’re admitting that this series is about the author demanding to be seen, and its appeal rests in a need for religious devotion. This series is dogma, in and of itself. Do you see it now? Do you understand it was never about you? You were never not good enough for this series.]

In this episode, as well as the last one, Evangelion has very carefully put the effect before the cause in its storytelling. In doing so, it obscures the cause as a thing that might drive the story. The spotlight on the effect becomes an effort to cut directly to the audience’s sympathy. Evangelion postures to engage with its audience on an emotional, tonal, and semiotic level – i.e. all the damn Catholic symbols absent any actual commentary on Catholicism – while simultaneously shutting down the paths where someone might have something to say about the structure and narrative.

The opening moments of this episode see Shinji calling Gendo on a payphone. Shinji’s school wants parents to attend a “future plans day.” This is a callback to episode seven where Misato formally took ownership over parental responsibility for Shinji – a fact probably forgotten four episodes later. The question at hand should be, where is Misato now? Why is Shinji in a position to call his father from a device whose cinematic existence is linked to isolation (despite the fact that Shinji has a cell phone) when he knows Misato is supposed to be filling that role? Because the writing is demanding an effect: feel bad for Shinji and never mind the internal inconsistencies.

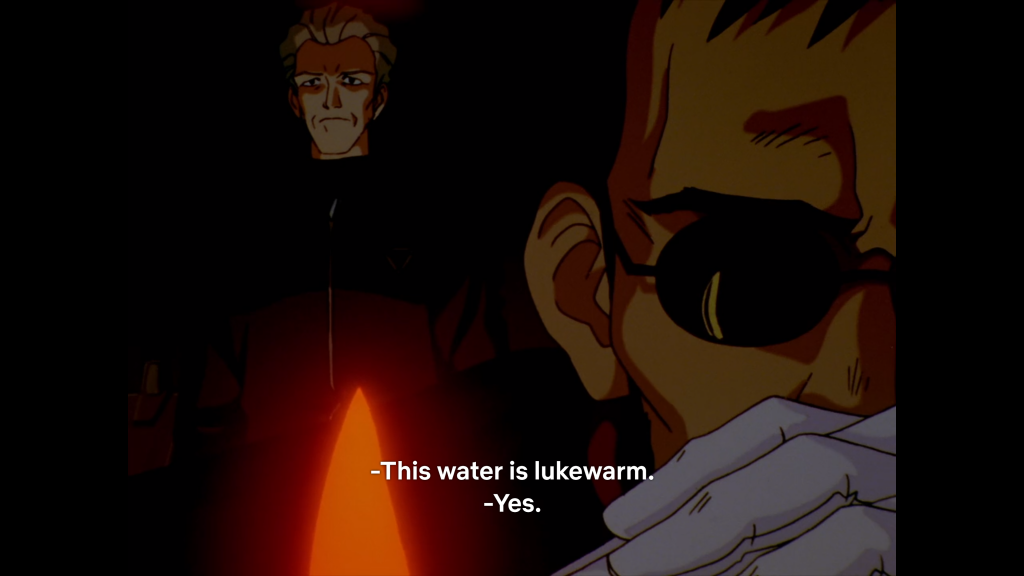

The cause is found in the layered reveal that Misato didn’t go home the previous night. The effect-cause beats make the audience a witness to Gendo telling his secretary to never put calls through from Shinji. Some scenes later, we see the coy revelation that Misato was having sex with her ex. While I take no exception to a story playing with the order in which things happen, the fact that none of this is revealed to Shinji and it has no impact on the would-be protagonists from either a conflict or character development perspective tells me that all of this is happening for the audience’s benefit. So, why? Why should the audience take a turn in the gym of emotional heavy lifting?

Why, when Misato and Kaji are stuck in an elevator, do we need to hear Misato complaining about how she is in a bad mood from waking up to see Kaji’s face? Why is picking a side between sexy step mom and weird “uncle” further drilled home with one of the NERV functionaries, whose name I have not bothered to learn because he’s not important, having ten seconds to whine to the camera about how Misato is too lazy to pick up her laundry? Again, she’s not lazy, she was too busy fucking, and we are supposed to pick sides. But, why?

Is it just a Chekhov’s Gun? Something to tell the audience that nothing should be treated as a throw away? Cool, but as I recall, the gun shot someone in the play. It wasn’t pointed at the audience. Sure, Misato running around with Kaji motivates Shinji to have some actual contact with his father. This is unpleasant for the lad, but it only underscores the dysfunction for the audience. Gendo being an ass is such old news to Shinji that it has no impact on him fumbling about amid the Tokyo-3 blackout.

So exactly how much psychoanalysis, of both myself and Shinji Ikari, is required in the name of criticism? It would probably be a bit peevish to say none. Yet I don’t think it would be wrong, either. This is not episode one. We are eleven, bloody episodes into this series. We are past the point where I will take things on good faith or shelter the series’ conflict in my head while the writing is limiting itself to striking overtures and punting mystery boxes.

[RN: I suspect I should be making mountains out of mole hills apropos of the angel’s attack looking like someone crying. Gendo hurts Shinji, and Shinji walks away from it without showing any emotions. Once we get into the battle, the alleged enemy deals damage through its tears. Shinji then destroys the symbol for sadness as an extended metaphorfor he deals with his own pain. I see it. I don’t find it particularly interesting. I certainly don’t feel the need to dive so deep into the series for this grain of authorial intent that a return from said depths will require significant time in a decompression chamber, lest I get the Bends. Nobody should have to work this hard for fucking Evangelion.]

Ultimately, there’s nothing new to take away from the soap opera in this episode. Shinji is perpetually caught between feelings for Rei and Asuka, not because he loves either, but because like most high schoolers he only knows 6 people. Asuka remains is a terrible co-worker. There’s also an upskirt joke at Asuka’s expense, because anime. And, most importantly, Ritsuko wipes away any potential consequences of Gendo’s shitty phone call. She tells Shinji that his father had faith in him and the other pilots arriving to take on Matarael, the ninth angel. It’s an obvious lie, because Gendo sweating to get the three Evas ready is more about him not having anything better to do while NERV is reduced to impotence amid sabotage from the inside.

[RN: there goes another mystery box sailing through the air.]

It’s also an unnecessary lie because we are a world away from crying Shinji. He is either so far down the well of NERV’s hodge podge manipulation or so effectively repressing his feelings while convincing everybody he is fine, that Ritsuko’s tease of parental approval is shrugged off as easily as it is offered. So what’s it doing other than sliding another knife between the audience’s ribs?

I am endlessly captivated by Evangelion’s ability to seem entirely mundane while being deeply layered. That being said, I question the extent to which these layers exist for narrative purposes. And with that said, I can already hear people crying out that I don’t get the point of this series. That I’m not nearly smart enough to comprehend the art at hand. Maybe you’re right. But isn’t that the hidden trapdoor to Hideki Anno filling Evangelion with vague allusion and symbolism. If the narrative isn’t engaging with itself so much as making me engage with it, then the extent to which one might be right or wrong in their interpretation is prefaced on their willingness to shape that which is intentionally amorphous. Evangelion becomes a 2nd year English seminar; therein, it’s not what you say that matters, it’s the heights to which you can buttress a wack-a-do house of interpretive house of cards.

Were I in a different mood, I could have made a case for the un(importance) of Asuka taking on the most dangerous part of the operation against the angel. This part of the review series could be filled with a thousand extra words on how Asuka’s veneer of pride drives her to seeing teamwork and relationships as transactional. This thread could then be woven into the hubris of Tokyo-3 as a city of science, followed by a divergence into municipal governance by networked AIs.

That’s right, a throwaway bit of dialogue tells us that AIs control the municipal government of Tokyo-3. The city’s elected assembly only exists to appease the optics of democracy. There is a lot that could be unpacked on that point, alone. But at the end of the day, I would be the one doing the work on municipal tyranny, not Evangelion and not Hideki Anno.

Mark this as the episode where Evangelion pulls the train into its ontological station. In The Still Darkness captures the motif of Evangelion asking who is the creator and who is the audience in the clumsy fashion of a second year film student that has discovered experimental cinema. While it is amazing that so much could be said about an episode that is mundane in its delivery and narrative beats, I fail to see the value in asking me to do the work.

This whole series feels memorable or forgettable subject to the whims and moods of the audience. While that could be said of all art, Evangelion’s approach feels different. It is more chronic in creating a vapid space where questions about its meaning are deflected back to the audience with the breezy tone of a guidance councilor saying, “You get out what you put in.”

I always hated the smug satisfaction of people who turned around questions on the person asking them.

[A note from a version of me who has finished watching the entirety of the series, for a third and final time, and is now free to connect the dots that past-Adam could not quite see:

In so much as a religious (i.e. generally intolerant, toxic, and needlessly aggressive) energy radiates from most capital F-Fandom, I think we’ve struck on something interesting at this point in the review series. What if Evangelion isn’t a narrative – what if it is dogma? Art as manifesto is one thing, I know how to process that. Hideki Anno mobilizing Evangelion as his own personal bible might explain a few things – not the least of which is obnoxious Evangelion fans popping up to explain things to me with the menacing energy of a 13th century French knight on his way to Constantinople.

Consider that the standard analysis of this series is that it’s a critique of Christianity and the creator’s relationship therein. What if this is actually Christianity revised per the prophet Hideki Anno. It would explain why this entire series stinks of demanding to be seen, while simultaneously shifting the burden of storytelling on to the audience.

What does it mean, Pope Hideki?

What do you think it means, my child?

Look, you can’t be a Protestant and a Catholic at the same time.

Evangelion as dogma has all the elements of a modern religion as appropriated from Judeo-Christian canon and apocrypha: a long suffering son; an aloof father; temptations of various varieties; a selection of betrayers and non-believers; weird takes on a woman’s sexuality; mystical whiff-whaff that seems vaguely familiar but doesn’t stem from any actual religion; external hegemony acting against the nouveau faith; many avatars and faces of the divine. I could go on like this.

For today’s purposes, Evangelion as a religion certainly explains why I never have, and never will, latch on to this show. There’s no place in my life for religion. It is nothing that enriches my existence on this planet. The irony is that the entire review series was born of the same cognitive reservations that bring people to religion. I thought there was something wrong with me for not seeing what other people do in Evangelion. I assumed it was some kind of boorishness or character failing. But if the series is an attempt at spinning a new gospel of mecha Mary and her son Shinji-Jesus-Hideki Anno, then the fact is I am never going to see my way to enjoying this series’ offerings. I’m going to bounce off it the same way I was bounced out of Sunday School as a 7-year old who wouldn’t stop pointing out contradiction and hypocrisy in scripture.

It was never me, Evangelion, it’s you.]

Pingback : Adam Shaftoe: Critic and Author » Revangelion: Part 16 – The Cruel Sickness Unto Death, and Then…