What is Neon Genesis Evangelion and Why you Should (not) Watch it

The problem with writing a deep cut, longest-form review of Neon Genesis Evangelion is that if you can’t trick people into reading it from the start, they have little motivation to dive in after missing the first twenty-thousand words. As an alternative, allow me to offer the following missive in lieu of proposing someone start from word one. The question at hand is a simple one: what is NGE, and why should you (not) give a fig leaf about Hideki Anno’s effort at anime-as-religion?

The perceived canon of anime-as-very-serious-art is rather limited in its scope. Its membership typically includes a handful of Hayayo Miyazaki features (probably Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke, and Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind), Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira, and Hideki Anno’s Neon Genesis Evangelion. These titles shape the broad strokes of what mundane artists and art critics, alike, see as anime being art suitable for homage and university syllabi. Ever an iconoclast, I disagree entirely, but you didn’t come here for a lecture on why artistic canons are tedious.

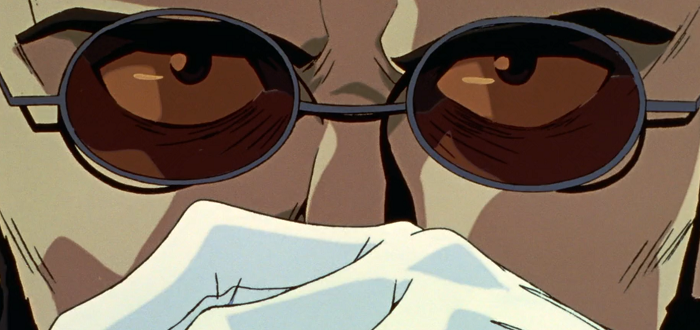

Evangelion fits snugly within this canon because it is ostensibly a story told at the intersection of (hu)man, technology, and Catholicism. Alas, nothing about Evangelion is so simple. The initial narrative of father-son hostility orbiting a robot, the eponymous Evangelion, that is purpose-built to save humanity from an alien/angelic other is largely a bait and switch. One signs up for mecha, only to receive a slice-of-life. Within the subsequently interpersonal story, the scope of the synecdoche makes itself known: Tokyo-3, the series’ setting, is the world, and the world is deemed unworthy by the series resident Bond villain and “World’s Best Dad”, Gendo Ikari.

It would be wrong to read Gendo as Hideki Anno’s avatar. While the truth of the series is known only to the enigmatic Janus of Gendo/Anno, the voice of the author – and source of endless auteurism that either derails the series or acts as its locomotive – is captured in the teenage nihilism of Gendo’s son, Shinji Ikari.

Thus, understanding Evangelon’s thesis demands one first imagine their teenage self in possession of the singularly adolescent belief that the world is darkness and nothing matters. Now imagine an artist building a religious text around the triumvirate of arrogance, self-indulgence, and genuine pain that drives existential crises emerging on entry into the adult world. That is Evangelion.

Evangelion is not a commentary on religion; rather, it is a dogma in service of an in-text and symbolic belief that while humanity is not beyond salvation, people, on an individual level, are baleful creatures. Humans are the cruel angels of the series’ theme song. Such is the hubris of Evangelion: the assumption that we, the audience, are only fit to harm each other, and that we as individuals are no better than Hideki Anno’s tormentors.

This premise builds to a final question from Hideki Anno: can we become something more divine (and kind) if we are removed from our individuality? Evangelion’s impenetrable and heavy-handed dogma exists in service of this question, which is ultimately answered with an entirely unsatisfying, “I guess,” on the part of Shinji Ikari. Yet such a forced decision is willfully blind to the notion that humans, both individually and collectively, are more complicated than a binary of good or evil. The teleology of Anno’s dogma blinds its creator to alternatives, likely because such paths are flawed for their inherent humanity.

This long and recurring arc of Evangelion’s metaphysical eye gouging is seen in how the narrative thread proposed at the start of the series (i.e. a boy unwillingly pilots a robot to save humanity from aliens) becomes so twisted as to be unrecognizable in the final act. A clear narrative premise is buried under the weight of bewildering, if evocative, world building. By the end, Evangelion is little more than a disjointed paroxysm of full-throated demands to be seen and cared for – both from the characters and within the subtext of the story, itself.

The ultimate question of Evangelion is the question essential to all dogma: do you want to believe? Are you willing to engage with this story as one engages with an ambiguous text in the Abrahamic tradition, replete with contradictions on sexuality, gender norms, love, wroth, filial duty, and the apocalypse? Will you accept the nature of sin via Hideki Anno? Will you forgive and in turn be forgiven? Will you unbecome to become something greater in the process? These are the fundamentals of Neon Genesis Evangelion; it is religious art, not art on religion, and that is why it is such a convoluted, didactic, alluring mess.