Revangelion: Part 16 – The Cruel Sickness Unto Death, and Then…

[retrospective note: I suspect my past-self wanted you to read the first line in this essay in the fashion of Hugo Weaving as Agent Smith.]

I’d like to share something of a revelation I’ve had about my relationship with this series. Partial inspiration for this project emerged from my belief that I had missed something fundamental to understanding Evangelion in a previous review. This drove me to taking on a task of absurd depth to show the world – and my own insecurity – that I am good at what I do. Fear of being seen as not smart enough is a powerful motivation in making a critic take on work they would rather not do. Skip ahead twenty-five thousand words, and I have come to a new hypothesis: what if the problem with Evangelion is that it hasn’t done a good enough job of making me care to understand it.

[retrospective note: flash back to part 11 of this series where I postulate that Evangelion is a dogma, accessible only to acolytes and inherently alienating to those not inclined to BELIEVE.]

In reflecting on this project, I can see how my willingness to give Evangelion the benefit of the doubt ebbed since the early episodes. Reframing Gendo as the villain of the story got some good mileage back in episode three and four, but there’s only so much that can be said along the lines of “the main character is not an honest narrator toward his intentions.” There has to be more to carry the series forward.

[retrospective note: like action, gradual character depth, or really anything at all beyond Gendo tenting his fingers as the story unfolds at a geriatric turtle’s pace]

This is how suffering materializes as a narrative catalyst. Everybody at NERV is not only working their own agenda, but they are also miserable and maladapted people. The problem with suffering is that it burns itself out. Audiences get inured to it. Yet that suffering is essential because only in suffering is the Human Instrumentality Project is born. And that, dear readers, is why I think I’ve always bounced off this series.

Let’s compare Evangelion to something a little more contemporary. In the season three finale of The Good Place, Eleanor Shellstrop asks Janet for the answer to the question of life, the universe, and everything. In her question, Eleanor is seeking hope. She needs to know that there is more to human existence than endless misery. I watched this exchange between Eleanor and Janet while on an elliptical glider, exercising my damaged body in one of the few ways that is still available to me. And as I watched Eleanor ask a question that has weighed heavily upon my thoughts during my post-cancer life, I struck upon the answer to Evangelion.

I don’t hate this show because I lack the ability to empathize with Shinji.

I don’t hate it because I’m a boor, who won’t do the work of learning a few hundred kanji while prepping a literature review worthy of an MFA thesis to accommodate this series’ singular and obtuse references after Catholic apocrypha.

I hate it because the answer to Evangelion is that humanity is a failed experiment.

I have had some very dark moments in my life. In defiance of those moments, I held to the notion that humanity is more good than it is bad. As a civilization, our default setting is not atrocity. Even though we may not be the best versions of ourselves, and we probably won’t get there in my lifetime, I have to believe that we can get there. Otherwise, what’s the point of getting out of bed in the morning? Why bother playing this game if humanity is nothing but malevolence and cruelty? The Good Place explores that struggle through a resolute belief that if an Arizona trashbag like Eleanor can be redeemed, so can humanity. Evangelion disagrees.

Evangelion takes suffering and uses it as a rationalization for why humanity can’t be redeemed. Shinji takes his pain and makes it the world’s problem, but behind that suffering is Gendo Ikari. Gendo pairs Shinji with people who present him with the polar opposites of love and hate, sometimes at the exact same moment, to keep him unbalanced. Ultimately, these relationships drive Shinji further into the torment of his own mind, softening him to Gendo’s need that he keep piloting Eva-01.

But who is Gendo to take his pain and suggest that it somehow makes him special enough to make decisions on my behalf? Who is he to presume that his belief that humanity can not be redeemed is any more authoritative than my belief that it can. You can end your mortal existence if you like, Gendo, turn yourself into LCL and become one with your dead wife/daughter-clone, but do not for a moment presume that I would join you there.

I think this is why, as the series has moved closer to going off the rails – an act heralded in this very episode with Shinji’s conversation with himself on a train – my general disposition toward Evangelion has been souring. The writing is collapsing its orbit around cruelty as a thesis. Meanwhile, I’m the guy who is burning his engines to get away from what it is doing. This series and I are, on a fundamental level, incompatible with each other.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m going to see this review project through to its conclusion. In part because I’m stubborn and I don’t like to quit things until the job is done, but also because I might still be wrong about Evangelion’s end game. Though if we consider the seminal event of episode sixteen, I don’t think I’ve missed much of the point.

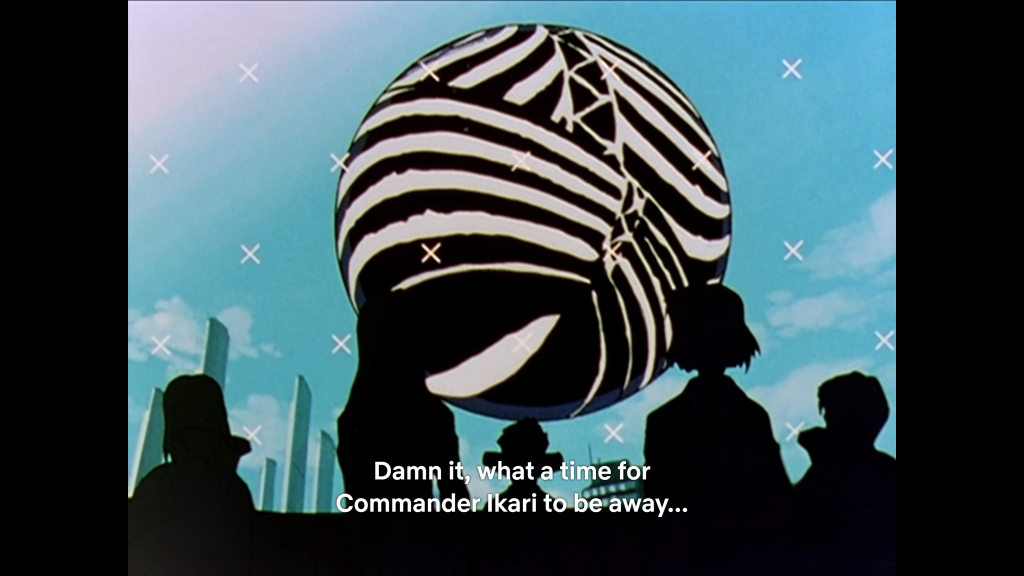

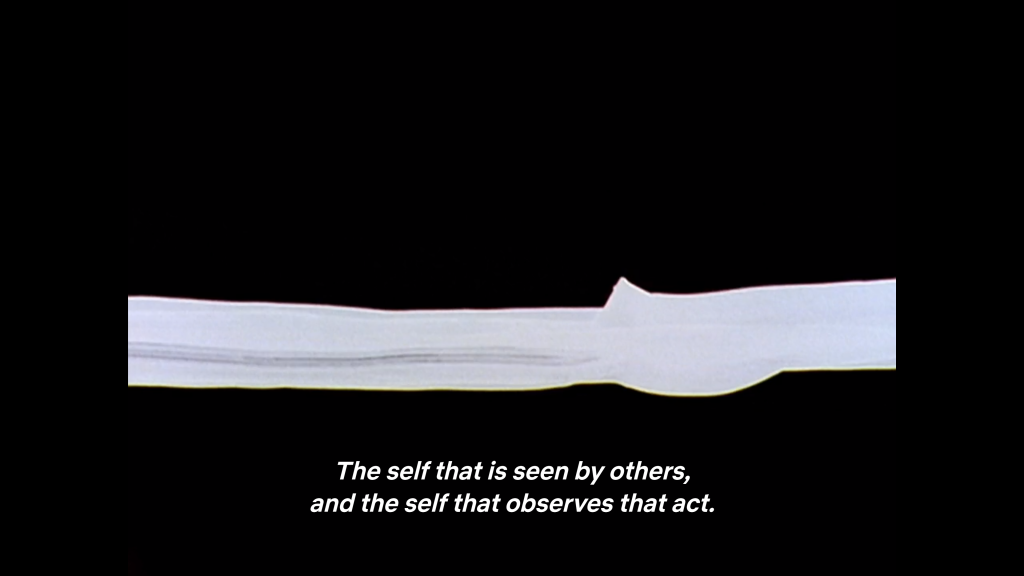

I’ll spare the usual approach to taking an episode apart and focus on a single sequence from this episode: Shinji talking to himself inside the multiverse/communing with Eva-01/having a psychotic episode. There is a lot to unpack in this sequence. Indeed, it is an MFA candidate’s delight of subtexts and nuances housed in a conversation where Shinji is represented as a vertical line on the screen and a more self-reflective version of Shinji is represented as a horizontal line on the screen. Gendo is not a line but one of those difficult to place zig-zag Tetris pieces, which seems about right.

The deep dive into Shinji’s mind shows a level of inner turmoil that is meant to be retroactively applied to everything the character has done to this point. Every smile, every joke, every moment of pride we get out of Shinji since he refused to run away back in episode four is meant to be parsed as a veneer. From where I sit, I can’t tell if it is a genius attempt at shading a long arc of development or a hastily constructed effort to slap some depth onto a character whose defining trait to this point had been going along to get along. Perhaps someone told Hideki Anno that nobody quite got what he was doing with Shinji and his suffering, and this episode was an attempt to (over)correct for the problem.

Intention aside, the episode frames Shinji’s inner thoughts as a debate between being honest with one’s self and building a persona around seeking external validation. The Shinji who is stuck inside a dimensional void, slowly dying in corrupted LCL as his Eva runs out of power – let’s call him Shinji Prime – believes that living his life in such a way as to prevent people from hating him is perfectly fine. Shinji Prime doesn’t see a problem with building his identity around being an Eva pilot, since that is the only thing that ever seems to get him any positive validation from the people in his life.

The inner truth Shinji, who might be another reality’s version of Shinji or could equally be the truth Shinji Prime feels pressing against his mental artifice in the last hours of his life – we’ll call him Bizarro Shinji – keeps poking Shinji Prime where it hurts. Shinji Prime recalls Gendo’s praise from episode 12, and Bizarro Shinji says, “You’re going to keep nursing that tiny bit of happiness for the rest of your life” Shinji Prime responds, “If I believe in those words I can go on living.”

This corrosive duality to Shinji’s nature establishes the last arc of Evangelion’s conflict: Gendo leveraging an exponential growth in Shinji’s suffering. Shinji’s inner struggle keeps him fighting the angels, so Gendo can reject humanity as a wholesale failure.

If my memory serves, there are four angels left over the next nine episodes, with the final two episodes being an unwatchable mess of beat poetry and “congratulations, Shinji.” It will be interesting to see how my personal revelation holds up against the balance of the series. Is there going to be more to the final offerings than suffering on display?

More importantly, I think I finally have an answer to a question I’ve been asking of this show for years: is it me, or is it Evangelion? In short, both. Evangelion is selling something that this guy is never going to buy.

[A note from a version of me who has finished watching the entirety of the series, for a third and final time, and is now free to connect the dots that past-Adam could not quite see:

Present-Adam doesn’t have much more to add to this post. Past-Adam did seem to think that Shinji was choosing Instrumentality for all human kind in the final episode of the series. However, the only thing the series makes clear in the final two episodes is that Instrumentality was happening and Shinji was along for the ride. His decision in the finale is to accept the gestalt of humanity or to let his self-hate keep him isolated from Instrumentality.

I have a few things to say on how Shinji’s about face on that front was entirely unearned and not satisfying, but I believe the union of past and present Adams cover that in another essay.]