The Pied Piper of Mars

There’s a lot that could be said about Elon Musk’s call to make humanity an interplanetary species. I’d like to begin my contribution to this conversation with a loud, wet, fart directed toward the-man-who-would-be-Hugo Drax.

Leaving subsequent details of broken wind to your imagination, dear reader, let’s talk about Mr. Musk’s vision. Tempting as it is to paint Musk as John Galt (or Andrew Ryan – read a book, you damn millennials) it’s too on the nose for my taste. I say that, and I’m sure someone with more brand recognition than yours truly is working on said piece for the Atlantic or Slate.

Musk’s vision, however ambitious, however inspiring, doesn’t change the biggest problem with Mars: Mars is a terrible place, and Musk has no respect for what that means. Granted, Mars is not as bad as Venus. Though, Venus is, for all intents and purposes, Hell. Mars may be a world removed (heh heh heh) from the awful Jovian moons, looking at you, Io, yet that’s not saying much, either. Besides, some of those Jovian moons might have water on/in them. Compared to Earth, Mars is a toilet. The whole solar system is a toilet compared to Earth. But since Mr. Musk was so kind as to treat the world with his unsolicited vision of Mars, let me tell you mine. First, the facts.

Other than at the equator, where daytime temperatures can get up to 35 degrees celsius, Mars is too cold almost all of the time. The martian atmosphere is 96% carbon dioxide and 2% argon i.e. totally unsuitable for higher order carbon based life. Mars’ gravity is a little more than a third of Earth’s – enjoy months of agonizing physiotherapy if you decide to quit Mars and return to a real planet. And if none of those things are deal breakers for setting up shop, Mars doesn’t have a magnetosphere. That means surface level radiation beyond fun things like flesh scorching UVA and UVB; I’m talking about gamma radiation.

With our current and foreseeable level of technology in play, the brave citizens of Musktopia – assuming the first wave of colonists don’t die in transit or go space happy – are going to be living underground. A new life awaits you on the off-world colonies, complete with an an air-locked, radiation resistant (you hope), SpaceX patented hole. Feeling nostalgic for some sun? Enjoy pouring yourself into an EVA suit and strapping on a dosimeter. Also, Mars gets about 40% of the sunlight we enjoy on Earth – seasonal affectives need not apply for Musktopian citizenship.

Though supply drops from Terra Firma should stave off the colony’s inevitable entropic death (fun fact, we can’t make artificial self-sustaining biospheres here on Earth) day-to-day survival will depend on a group of people, all of whom bought their way into Musktopia, working to maintain homeostasis for every waking moment of their lives. Even on a good day, consumption of power, air, water, and food will need to be heavily regulated.

Do you know how they wash clothes on the International Space Station? They don’t. They wear the same clothes until the funk is unbearable. Then they blow the offending clothes out the airlock to burn up in the atmosphere. Perhaps Mars will allow for some sandblasting of soiled garments. That’s assuming they have the power to cycle the airlocks, recharge EVA suits, and keep the outdoor lighting on. Consider the utilitarian horror that would come with severe and prolonged rationing should the colony fall from homeostasis with the Earth at an inconvenient position relative to Mars. I have two words for you: Donner Party.

A brave vision of the future? Fah. A Mars colony c. 2030 would look like Dmitry Glukhovsky’s Metro 2033. Without a serious upgrade to our current tech level, a near-future Musktopia would be a world of darkness and entropy. It would be a place where life is cheap and death is common. Mars may not have the radiation monsters of Metro, but not a single person in that colony wouldn’t live in fear of a terminal dose of the hard stuff leading to a slow, painful death.

A brave vision of the future? Fah. A Mars colony c. 2030 would look like Dmitry Glukhovsky’s Metro 2033. Without a serious upgrade to our current tech level, a near-future Musktopia would be a world of darkness and entropy. It would be a place where life is cheap and death is common. Mars may not have the radiation monsters of Metro, but not a single person in that colony wouldn’t live in fear of a terminal dose of the hard stuff leading to a slow, painful death.

Still want to go to Mars within the next twenty years? Feeling confident that Mr. Musk can innovate his way around the challenges of living on a barren and lifeless rock? Then allow me to introduce you to the nature of things going wrong in space.

On March 18, 1965, Soviet cosmonauts Pavel Belyayev and Alexei Leonov were launched into space aboard the Voskhod 2. Leonov’s mission was to conduct the first ever space walk. This brief foray into low-Earth orbit met with near-catastrophic failure twice, and then the cosmonauts almost died on Earth. The first problem occurred when Leonov’s space suit experienced an unforeseen problem. Upon being exposed to the hard vacuum of space, the suit ballooned up such that Leonov couldn’t squeeze back into the Voskhod’s inflatable external airlock. Here’s the story in Leonov’s own words:

“With some reluctance I acknowledged that it was time to reenter the spacecraft. Our orbit would soon take us away from the sun and into darkness.It was then I realized how deformed my stiff spacesuit had become, owing to the lack of atmospheric pressure. My feet had pulled away from my boots and my fingers from the gloves attached to my sleeves, making it impossible to reenter the airlock feet first.I had to find another way of getting back inside quickly, and the only way I could see to do this was pulling myself into the airlock gradually, head first. Even to do this, I would carefully have to bleed off some of the high-pressure oxygen in my suit, via a valve in its lining. I knew I might be risking oxygen starvation, but I had no choice. If I did not reenter the craft, within the next 40 minutes my life support would be spent anyway.

The only solution was to reduce the pressure in my suit by opening the pressure valve and letting out a little oxygen at a time as I tried to inch inside the airlock.”

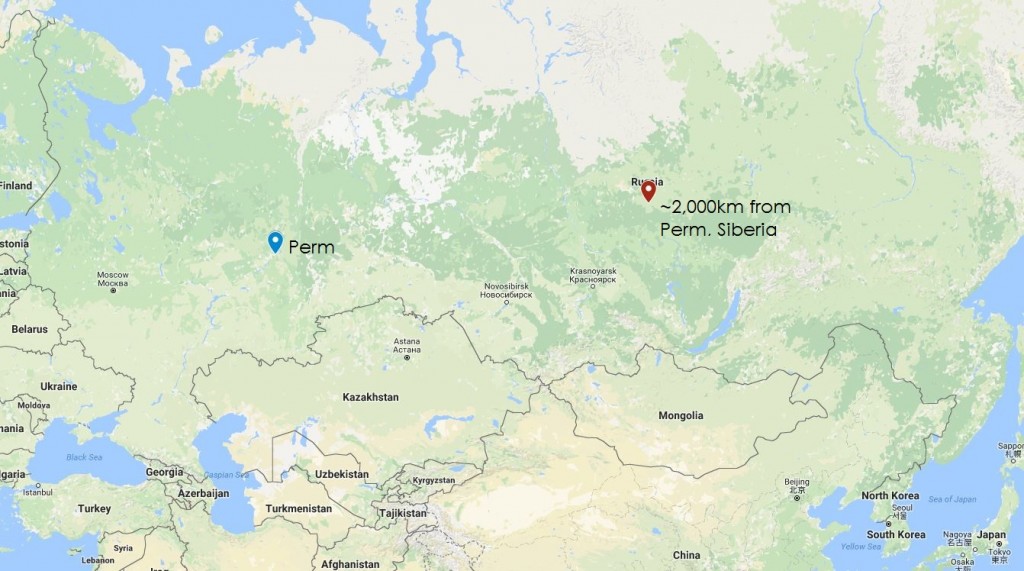

Once Leonov was safely settled into the craft, he discovered the automatic guidance system had failed. Leonov had one orbit of the Earth to plot a seat-of-the-pants deceleration burn and landing. He aimed for a city called Perm in the Ural mountains. He probably would have hit the mark had the lander and orbiter properly separated prior to the engine burn. A single unsevered communications cable acted as a tether between the two vehicles, throwing the conjoined ships into a 10G spin as they entered the atmosphere. When friction and tortional stress finally broke the cable, the lander came to ground 2,000 kilometers from Perm in Siberia, in March.

“We were only too aware that the taiga where we had landed was the habitat of bears and wolves. It was spring, the mating season, when both animals are at their most aggressive. We had only one pistol aboard our spacecraft, but we had plenty of ammunition. As the sky darkened, the trees started cracking with the drop in temperature—a sound I was so familiar with from my childhood—and the wind began to howl.”

At the time, Moscow had no idea where Leonov and Belyayev landed. Soviet listening posts, had, however, picked up their rescue signal. Civilian aircraft were the first to zero in on the landing site. They dropped wolfskin boots, clothes, and cognac. Leonov and Belyayev spent forty-eight hours in the woods, MacGyvering supply drops and their space suits into dry clothing and blankets. Even after the military found them, they had to ski nearly ten kilometers through primordial forest to a clearing where a helicopter took them back to civilization.

Why tell this story? How is it relevant to a mission to Mars? Because everything that went wrong for Voskhod 2 was the product of small, unforeseen failures leading to potentially catastrophic ends. Even with thirty years of experience making pressure suits for pilots on Earth, the Soviets’ first space suit functioned in a way that could not be predicted. Then, a single unseparated cable, probably the result of bad explosive bolt or a faulty switch – a fifty kopeck part, to borrow a phrase from Liam Neeson in K-19 – led to the mission landing 2,000km from their target area.

Elon Musk paints a great picture of space, but history teaches us that space isn’t about the message – even in the Soviet Union. Space is about surviving in a place utterly hostile to human life. That survival is governed by thousands and thousands of small details working together in such a way that people don’t die and equipment doesn’t go screaming down a gravity well at 200 m/s.

Setting up a colony on Mars takes the challenge of space, as we know it, and adds ten thousand new problems to the equation. Some of those problems are literally beyond our current ability to solve. Moreover, a colony needs more than mere survival against the elements; long-term colonization means we would need to thrive in a place intent on killing us. Such a challenge demands a level of detail-oriented thinking that Elon Musk is content to glaze over in the name of a call to action.

How do we keep 100 people alive in a homeostatic environment on Mars when we’ve not yet done it on Earth? Will the application of free market economics in terms of “buying a ticket” ensure the colony has sufficient skill sets to cope with the unknown? Recognizing that people only do things for the promise of reward or out of fear of punishment, how will Musktopia ensure everybody does their part for the colony? How does one protect civil and individual rights in a place governed solely by the Outer Space Treaty? What happens if birth control fails among the colonists? What, you don’t think there will be space fucking? There will be space fucking.

Mars presents challenges of engineering, agriculture, chemistry, sociology, economics, and ethics. These are not questions to be dismissed as the sour grapes of nay-sayers or the fiddly details of backroom boffins. Grand colonial ventures on Earth have a storied history of catastrophic failure at the cost of human life (and success at the cost of even more life) because there was too much vision and not enough planning. And suppose we find evidence of life on Mars? I don’t mean Martians, but life that might evolve into something multicellular in a few million years. What right would we have to Mars if something else called it home? Could we be trusted to steward a second world when we’ve done such a poor job with this one?

By all means, let’s go to Mars, but let’s not make the mistake of following Elon Musk there, even conceptually, when his call for Mars is informed by no great achievement here on Earth. In fact, his claim should be met with skepticism considering Musk’s private-sector space industry is looking a little shaky in the wake of a Falcon 9 exploding on the launch platform and the US Congress demanding a formal investigation. His appeal to our innate sense of wonder serves to mask the sort of “private sector does it better” nonsense that so frequently comes from the spray tan stained lips of Donald Trump. At best, Musk’s plans are a pipe dream; at worst, they are a distraction for SpaceX’s investors.

Space is a cruel mistress. It has zero fucks to spare for people who think that “sorting out the details” comes after the visioning exercise. Also, I would hope space has zero fucks to spare for people who unironically use the word “visioning exercise.”