Adios, Cowboy: Review 6 – Sympathy for the Devil

The Simpsons’ famous monosyllabic, “meh,” should best encapsulate of my feelings on Sympathy for the Devil. On the surface it is a routine unit of television. Dare I say, this is Cowboy Bebop’s first foray into the tedium of the police procedural. There is no parallel plot, nor is there anything that might stand out as “jazz” of any sort. The closest it comes to having a narrative ambition is a dram of transparent misdirection that seems beneath the dignity of the show.

On deeper reflection, the episode leaves me feeling conflicted. The episode may be plodding and predictable, but it’s also richly layered and dripping with potential. For the life of me, I can’t figure out how these things are coexisting together. In trying to work through this problem, I now see this episode as something that invites an existential sort of conversation on the strengths and limitations of “Space Jazz,” the self-defined genre in which Coboy Bebop lives.

Since word-one I’ve asked if this show has a plan. Ballad seems to have demonstrated the answer to that question is yes. This revelation leaves me hungry to determine the extent to which Space Jazz can weave its plan when its stated purpose is to challenge, and ostensibly reject, Space Opera’s traditions and functions. Does Space Jazz require planning beyond the next bar on the sheet music? The next page? The next movement? Perhaps Cowboy Bebop is little more than a string of connected motifs, ill-defined beyond a general sort of theme and unfolding on a whim rather than according to any sort of plan. Then again, the trick at hand might be to make Space Jazz seem chaotic until the final note is played. Only then does the intention make itself obvious. To borrow phrase from another golden child of 90s television, I want to believe. I want this series to be building to something that will knock me on my ass. But I’m not quite there yet.

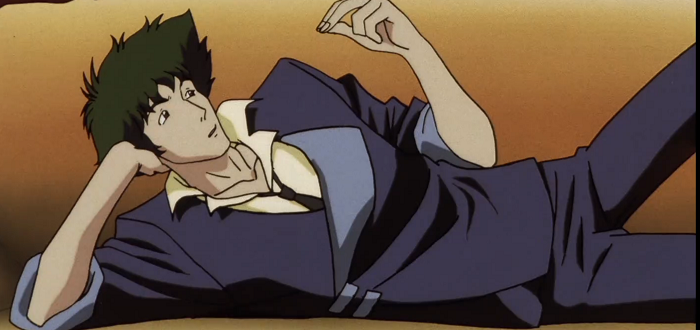

Sympathy for the Devil’s first scene suggests there is an even deeper story to Spike than what was revealed in Ballad of Fallen Angels. It opens with the invocation of biological terror: a cabal of masked medical types preside over a naked body. It’s hooked up to banks of machines whose tubes illicit an uncomfortable techno-organic hodge podge, as if the HVAC of Brazil were wired up to a person. Rough hands force open an eye with all the intention of A Clockwork Orange’s Ludovico technique. Banks of organs in jars and a mysterious blue orb invite the audience to speculate if the assortment of guts have been extracted or await implanting. Then, a sharp camera zoom reveals the body on the table to be…Spike. What’s the relevance of this dream to the rest of the episode? Zero.

Does that mean we should write off this dream as something pointless? Is Space Jazz so in love with breaking convention that it would insert a grotesque but meaningless nightmare into the episode as a red herring? When Vicious says that the same blood runs through him and Spike, is it such a conceptual leap to believe that the two of them are syndicate experiments in creating Blade Runner style Replicants? The conventions of Space Opera would certainly suggest the game is afoot. I don’t know if Space Jazz is playing by the same rulebook.

The central conflict of Sympathy for the Devil only adds to this confusion. It provides rich evidence of a sinister backstory within this universe, but does so in an entirely mundane fashion. Therein, a case of mistaken identity leads to yet another blown bounty.

Hey, kids. It’s me, Critic Adam. How in the hell do Spike and Jet stay in business? After six episodes, they have yet to earn a single Woolong. I point this out in full consideration of a show that includes the words, “street sense” in its manifesto. From the audience’s vantage, we see a lot of hustle and very little payoff for the main characters. Here I thought the 90s were supposed to be less pessimistic about the painful nature of freelancing. I guess some things never change.

Returning to the point at hand, the episode’s single plot is about a boy called Wen who is, effectively, immortal. In another Bebop first, swaths of Sympathy’s screen time are dedicated to slow exposition on Wen’s back story. Half an act is spent showing how a hyperspace experiment on Luna led to devastation on Earth, which made Wen, and seemingly nobody else, eternally young and immune to death. Spike’s response to this child is to put a magic bullet in his brain. This choice treats the audience to an Akira-style show of body horror as Wen rapidly ages and dies. My first question: why spend all this time and back-story on a throwaway character when the main cast seem unworthy of such attention?

Space opera conventions would have me believe that there is a shadow force of immortal children – because Jet’s technobabble says the immortality rays that affected Wen would only work on children – who are the controlling power behind the solar system. Common sense says that if a hyperspace event on Luna could alter one child on Earth, it should do the same for many others.

But Cowboy Bebop is persistent in reminding the audience of its desire to ignore not only the broader conventions of the genre, but the style and framework that it, itself, has created. If experimentation and improvisation are at the core of jazz, should I believe that Space Jazz is any less inclined toward throwing an idea out on the table as a one-off before moving on to something that sounds better? This indifference, this painful desire to be cool, is what makes it hard for me to believe there is a deeper game at hand.

Cowboy Bebop has put me in a space that intersects alienation and engagement. With the ethos of Space Jazz back-dropping my response to each narrative twist, I can’t be sure that the typical patterns one looks for in criticism mean what I think they mean. A do nothing episode set against over-the-top world building has me so far out of my comfort zone that I would willingly unlearn what I have learnt if I had the faintest idea what Cowboy Bebop wants from me in return.

In fairness to the show, I should say that the state of popular culture would be better if more shows put us in this sort of place. Interpreting Cowboy Bebop speaks to addressing subtle twists of story and theme. No middling piece of crap show can manage to feel both routine and decadent. Despite this decadence, the first six episodes reflect a show that is content to faff about in the shallow end of the pool. First principles are well and good, but at some point a story has to do more than show off its potential, particularly when it has demonstrated how that potential can be applied to something exceptional. I know this series has a plan. I know it is building toward something. With a quarter of the show behind us, it is time to get out of the first act and invest in a bigger conflict.