Adios, Cowboy: Review 10 – Ganymede Elegy

In the year 1560, a poet by the name of Joachim du Bellay died in the city of Paris. Some years before his death, he authored a poem on the passing of his cat. My life is enriched by the knowledge that adoration of one’s cat is not a novelty of the twenty-first century.

And of course I’m going to give you the text of Elegy on His Cat:

I have not lost my rings, my purse,

My gold, my gems – my loss is worse,

One that the stoutest heart must move.

My pet, my joy, my little love,

My tiny kitten, my Belaud,

I lost, alas, three days ago.

Welcome to an Adam Shaftoe project. Any jerk can define the elegy using writers like Thomas Gray, W. H. Auden, or Dylan Thomas. Only I give you a Frenchman upset over the death of his cat: something infinitely more relatable than Auden banging on for four stanzas about the provinces of Yeats’ body. Get out of here, Auden. Nobody wants you when there are French poets talking about cats.

Ganymede Elegy is a Jet episode. It sets aside the traditional opposite plots for a story that acts as a monument to the life Jet left behind on Ganymede. Even when the point of view shifts to Spike, there is no second narrative. Everybody is a player in Jet’s act of self-elegy, except for Faye. Faye is literal set dressing (or lack thereof as most of her screen time involves the application of tanning oil and a bikini designed by the Versace House of Anime Fan Service).

For real, when is Faye going to become an actual character on this show? After ten episodes she remains little more than a mobile vector for delivering snark – which I of all people should be able to appreciate, but I don’t because she’s an asshole to Ein. I’ll invoke the immortal words of Michael Scott, “why are you the way you are?” People have told me that Faye’s turn is coming. All I can say for now is that the show needs to do something very special to make me see past a character whose acerbic narcissism knows no bounds.

For Jet, the episode is a reckoning with a home, ex-lover, and life he left behind seven years before the start of the episode. And points to Bebop for making it clear from the outset that Jet and his former lover, Alisa, would not be getting back together. This episode is a memorial for Jet’s nostalgia, not some sort of tacky rom-com. It honours the memory of Jet’s past rather than resurrecting it, but that’s all it does. In keeping with the eponymous poetic form, Elegy is deeply reflective on Jet’s character, and not much else.

This is fine, but it really feels like something that should have happened ages ago. Appearing as episode ten makes me think someone raised the point of not knowing anything about Jet in a production meeting. The result was a scramble to give Jet some long-overdue history.

Within the episode, a handful of recurring artefacts and metaphors sketch out Jet’s odd relationship with Ganymede. First, there’s the watch that Alisa gave him when she ended their relationship. In addition to being the physical manifestation of Ganymede’s hold on Jet, it is a reminder that Cowboy Bebop revels in denying agency to its characters.

You see, Jet’s decision to leave Ganymede after Alisa abandoned him was only tangentially his own. He recounts his past-self announcing an edict amid an empty house: if Alisa did not return to him by the time the watch broke, he would leave Ganymede. If I may be so bold, that is both passive-aggressive and a really convoluted way for one to decide to get on with their life after a break-up. Yet with a single stroke of the pen, the writing lays Jet’s life of “living and wandering with a group of weirdos” at Alisa’s doorstep.

Relationship pro-tip: never be this guy.

The episode does its best work when it is forcing Jet to come to terms with the narcissism inherent to his memories of Ganymede. Both Alisa and one of Jet’s old cop buddies are positioned to remind him that life continued on Ganymede without him. For example, Jet seems genuinely surprised when he learns his old cop buddy is still a cop. It is as if Jet leaving the force meant all his friends stopped being cops.

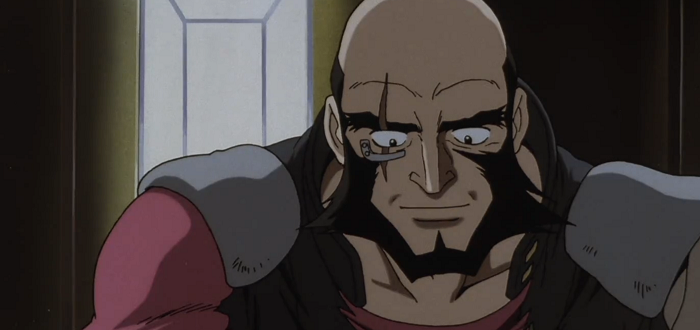

For her part, Alisa became a bar owner, found a new boyfriend, and has zero interest in nostalgic crazy making. When Alisa’s boyfriend, Rhint, transforms from an off-putting weirdo into the episode’s main bounty – the first was caught off-screen and claimed within the first five minutes – we see Jet begin to shed the fantasy of home he fostered since leaving the Ganymede PD/ISSP and becoming a bounty hunter.

When Jet joins the pursuit on Rhint and Alisa, Spike gives voice to the audience’s big question: is Jet going to blow this bounty out of past affection for Alisa? Jet’s commitment to collecting the modest ₩1,800,000 bounty on Rhint is suspect right up until the very last moment. In the end, Alisa gives Jet a taste of the closure he wanted (and we can say a lot here about the tropes of male fragility playing out on screen) and in doing so sealed Jet’s resolve to turn Rhint over to the cops. I know what you’re thinking: this doesn’t make sense, and it shouldn’t work.

Jet and Alisa’s relationship ended because Jet couldn’t make space for Alisa to be her own person. In her words, he treated her like a child, refusing to let her make any decisions. She left because she wanted a life where she had, wait for it…agency. Even though the episode shows us that life on her own is something of a shambles, leading to her boyfriend murdering a scumbag loan shark, it is a shambles where she had control.

On the one hand, I feel like this is the episode attempting to do something that rises above the Spice Girls feminism of the 1990s, but I’m not quite sure how well it manages the landing. Is the episode saying the deck is stacked against a single woman on Ganymede? Maybe, but since this is Jet’s elegy for the world he used to know, we will never know. Within the context of Alisa on Ganymede, the message is muddled because the show is trying to bury the place it is introducing.

The coda to this emotional outpouring is Jet telling Rhint to, “be strong for her.” Cut to the next scene and the Ganymede PD are hauling Rhint away – though Jet explains that the charges are likely going to be blunted since the cops are inclined to see Rhint’s actions through the lens of self-defense.

The conclusion of the episode shows a character true to his original purpose. Jet wanted to understand why Alisa left him. There’s no great revelation, no moment of change, when Alisa gives him this answer. It’s a human moment, not a dramatic one. Jet’s final act of stoic departure from the illusion of Ganymede was to toss the broken watch into ocean that covers the moon’s surface. His final words, “time is flowing along,” stand as the last line of the elegy.

I find myself going back and forth on Cowboy Bebop because it seems afraid to give the audience episodes like Ganymede Elegy or Waltz for Venus. I can see the value in experiments that keep the main characters an arm’s length from any influence over their story, but these last few episodes demonstrate that the show can work when it puts its characters in more conventional narrative settings. Granted, I would rather see more of an arc on how episode feeds into the next. But compared to the likes of Gateway Shuffle, I’m content with a stand-alone episodes like Ganymede Elegy.