Adios, Cowboy: Review 15 – My Funny Valentine

Well I knew this day was coming. Eventually, Cowboy Bebop would get around to giving me a Faye episode. In advance of this particular story, the writing has done everything it can to make me not give a single solitary toss for Faye’s history. Remember the time she ate a can of dog food, the last can of dog food, in front of Ein and left him with nothing? Or how about when she decided to try and kill Gren? If Faye had things her way, the Bebop would have left Ed on Earth despite Faye promising Ed she could join the crew. Faye is, by every measure that matters, a terrible human being we should want to blast out the nearest airlock.

My Funny Valentine’s purpose is to show the audience the events that shaped Faye into a cynical and self-interested bounty hunter. The task for the audience is to decide if a person’s past experiences stand as a shallow rationalization for terrible behavior or essential context to understanding personal trauma. Is this episode the culmination of Faye’s life, or is it a chance for her to put a bracket around her past events begin again?

Bearing this question in mind, MFV triples-down on the series’ ongoing exploration of personal agency. However, the moral ambiguity inherent to Faye’s character suggests that Cowboy Bebop has graduated from its early lessons in alienation. The tricks of passive plot structure and endless reductio ad absurdum repetition are nowhere to be seen in Faye’s story. The episode even begins with Faye in a humbled position, something entirely new for her character. Ein gently attempts to wake Faye up from a nap because he needs his dog mat (i.e. the thing he poops on) cleaned, which she begrudgingly does. We’ve seen a lot from Faye, and I’ve come to expect a certain range of behavior from her character. Tending to poop was not on that list.

After carrying the mat to the bathroom, with Ein following close behind, Faye decides to tell the dog her life story. One might be tempted to roll their eyes at this moment of vulnerability as something forced and contrived – something that is little more than the writers throwing darts at the board to determine a mechanism for humanizing a generally unlikable character. Here is my counterpoint: if you’ve never felt so alone that you could only talk to an animal, then you’ve lived a charmed life. I don’t know that my counterpoint means the writing is good, but I can at least recognize the intention of the writing.

In addition to showing Faye as someone stripped of all agency, the details of Faye’s origin story call back to a number of previous episodes. Recall Faye saying she’s older than she looks. My Funny Valentine reveals that at age 20 she was put into cryogenic suspension, only to emerge more than fifty years later with no knowledge of her childhood or youth. The scene that shows Faye going into cryo evokes memories of Spike being worked on by the Brazil-esque medical team in Sympathy for the Devil. It shows her surrounded by medical technicians, a lifeless body within a frozen sarcophagus that is being unceremoniously slotted into a gap amid dozens of other deathless caskets.

Upon returning to the land of the living a mostly naked Faye, still dripping wet with cryo goo (the image is as unsettling as it sounds particularly in light of the POV camera work that shows Faye starting at her own boobs while a doctor hovers over her), is hit with a singularly American problem. The insurance company/medical corporation that bankrolled Faye’s mysterious treatment and incarceration in cryo would very much like to be paid for their services, with interest, to a total of ₩300,000,000. There is something to be said for a Japanese story channeling the singularly American problem of being unable to pay one’s hospital bills such that insurance companies hire bounty hunters to collect on the debt.

If emerging into the world under the burden of an unpayable debt, simply because one didn’t die, weren’t bad enough, Faye then gets hustled by her would be lawyer turned boyfriend, Whitney Hagas Matsumoto. Whitney, after convincing Faye life is worth living because she might fall in love with someone (pardon my wretching), fakes his own death and saddles Faye with his own debts adding another ₩30,000,000 to her ledger.

Let’s take this knowledge and recall Faye’s rule from Toys in the Nostromo Attic. Faye tells the audience that nothing good has ever come to her from trusting people. Given that Faye’s entry into the world comes with the threat of debtor’s prison and a hustle from a man she was falling in love with, I can certainly understand her worldview. Likewise, I can see why whenever she gets money she heads to the casino. The only place the laws of gods and men do not apply to money is in a casino’s bank.

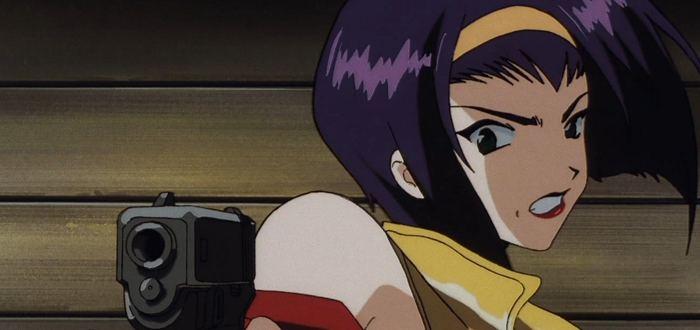

The bigger question, however, is do we, as an audience, accept this back story as a rationale for Faye’s actions? One “rule” of writing I tend to keep in mind is that an audience follows their sympathy. This is why Ed and Ein are immediately likeable characters. There’s no denying that the writing is clever in the way it shows Fays actions over the last dozen episodes as consistent with the revelations of MFV. She’s a woman stripped of agency and identity. The only things she has to her name are the clothes on her back, her ship, and her gun. Her bitterness toward her lot in life is one of the only things that is truly carried over from episode to episode. Faye’s disposition shows how these stories don’t exist in a void. It hints there is more to each individual episode than so much Seinfeldian nonsense. But sympathy requires that I be able to see myself in Faye’s character, and I think that is a bridge too far.

So here’s the alternate pitch. What if the episode doesn’t want the audience to give Faye a free pass for being bitter and jaded. In a round-about way, I think it knows she is a garbage person. Through that lens, the episode might exist to frame a comeback. I see this potential in Faye and Whitney’s reunion.

While Faye was spilling her guts to Ein, Jet was off hustling a bounty. That bounty was none other than Whitney Matsumoto. Faye promptly springs him from the Bebop, which leads to a space battle between Jet and Faye.

On a related note, how is it that the Bebop crew always have money for ammunition and space fighter fuel, but they never have anything to eat? Surely to god they could steal a few woolongs from the “causal space battle” line item in their budget and allocate it to some ramen.

During a lull in the battle, Faye demands Whitney tell her who she was before going into cryo. Whitney confesses, after some grandstanding, that all records of Faye’s life were lost in the Earth-Luna hyperspace accident. Before Faye can press for more details, the ISSP patrol that had come to collect Whitney from Jet reveals itself as none other than the doctor and nurse who fished Faye out of cryo.

The scene adds nothing more to Faye’s backstory and stretches the limits of plausibility. The doctor does leave Faye with a mote of wisdom before fleeing from the actual ISSP. He says that she might not have a past, but she does have a future. He further adds that only pubescent teenagers and people who are bored spend their mental energy trying to figure out who they are and what their purpose is in life.

Contrast that claim against post-Cryo Faye having a meltdown and proclaiming that she didn’t ask to be healed and stored on ice for fifty years. Few things are more petulant and teenager-ish than someone proclaiming they never asked to be born, probably while angry at their dad. It’s for that reason, I submit that this episode is neither an apology or a rationalization for Faye, but her call to action.

Is it a good episode? Well, there’s no doubt it is engaging, and it certainly casts aside doubts that Cowboy Bebop is doing things with a complete disregard for meaningful intention. I’m also more engaged with Faye now than I was at the end of Jupiter Jazz. But I still feel like it’s a strange choice to begin a character’s growth arc more than half way through the story. Faye’s relationship with someone like Gren, a person driven to reclaim the truth of their past, might have resonated more if the audience knew Faye lived without a past. Perhaps the best thing to do is borrow a phrase from Pokémon: it’s sort of effective.