Beholder: Reviewed

There is a balancing act that games like Beholder and Papers, Please have to manage in exploring the civil servant within a Soviet-style setting. Too much sympathy risks making the game an apology for the instruments of surveillance and oppression. Likewise, an excess of history’s grit can turn a game into a sermon. Warm Lamp Games’ Beholder manages this particular tightrope walk through its appeal to the fundamentals of human empathy and justice.

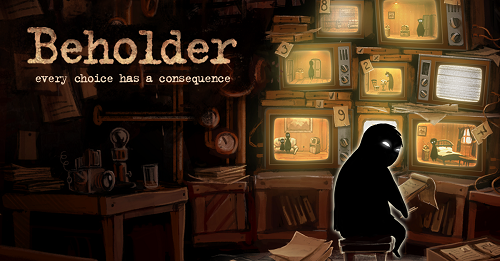

There’s a raw aesthetic to Beholder’s art and story. The characters are designed as abstractions of the human form. They’re recognizable from each other by the trappings of their profession: the doctor with his glasses and pocket watch, the landlord with his keys, the police with their angular eyes and truncheons. The opening cut scene is a masterful backdrop to an allegory for a nightmarish take on Brezhnev’s Russia.

Therein, Carl, the player character, and his family are relocated to a new city. Carl’s orders are simple: take over as landlord of an apartment block while serving as the eyes and ears of the state. This briefing is intercut with scenes of the police beating the previous landlord within an inch of his life. If Papers, Please made players ask, “What have I done?” Beholder finds its voice by making its audience ask, almost from the outset, “What have I got into?”

Beholder’s gameplay is generally straight forward, as not to overshadow its story. As landlord and spy, Carl must ensure his tenants’ actions, behaviors, and thoughts are in line with the party’s ever changing whims. This would be an easier proposition if Carl didn’t have to work where he lived. A player’s choices must subsequently balance the needs of the state against the demands of the tenants, including Carl’s family. Attempting to equally manage all three elements is where things started to go wrong for me.

My first mistake was expecting a fair system. I assumed that if I towed the party line, I could bend the rules just enough to keep my job while also helping my wife pay the bills, funding my son’s education, and ensuring my daughter has access to the illegal Western medicine she needs. So I reported on the tenants. I spied through keyholes, installed cameras, and filed reports on seditious activity. For my efforts, I was provided with just enough money to see my son turn to a life of crime and watch my daughter die of a lung infection.

On my second play through, I tried to turn Carl into a paragon of state virtue. I rummaged through apartments when tenants were out, desperate to find things to report. I even embraced the corruption inherent to totalitarian bureaucracy and stole the odd trinket to sell on the black market. It worked well until the police caught me stealing – I guess we know who watches the watchmen – and I had to pay them off. When I called the government to ask questions, as to be a more effective stooge, I was fined for not knowing better. Worse still, my family and tenants grew to hate me.

No matter my actions in Beholder, the people around me seemed to suffer. Negotiating some of the most basic tasks felt like impossible puzzles. I made more progress in subsequent efforts, but even when I knew what not to do, there remained a resentment against the systems of control operating against Carl. Even an hour with Beholder was enough to show that under an oppressive regime, a person’s best probably won’t be good enough.

As easy as it is to compare Beholder to Papers, Please, the former’s emotionally-charged fatalism makes it stand apart. Papers, Please allows the player to embrace a measure of doublethink as a cognitive shield. The person working as the border guard in Aristotzka isn’t necessarily an antagonist. The state’s slavish dedication to bureaucracy and protocol, even in the face of human suffering, is the enemy. There’s a professional shield to being complicit, or resisting, in Papers, Please.

Beholder’s humanization of Carl’s family and the building’s tenants generates an emotional through-line that strips the player of their ability to dissociate themselves from the consequences of their actions. Is keeping Carl’s son in university worth extorting a person whose only crime is breaking a law that doesn’t make sense? What about the next step? Which crime against the state or crime against the privacy of the building’s tenants is a bridge too far?

There are no simple answers to these questions in Beholder. The game is a complex tapestry of relationships between Carl and the people in his life. A player might fail to meet win conditions in the traditional sense of the word, but failing in Beholder is not a fruitless exercise. In failure, and success, one sees the cost of dictatorship and turning citizens into the enemy of the state.

And on that note, let’s take a beat to think about where this game is coming from. Warm Lamp Games is a Russian studio. Alawar Entertainment is a Russian publisher. A Western audience would do well to recognize that this game is probably walking a very fine line terms of its social commentary. In uncertain times, art and courage can be one and the same. Think on this idea as you play Beholder.