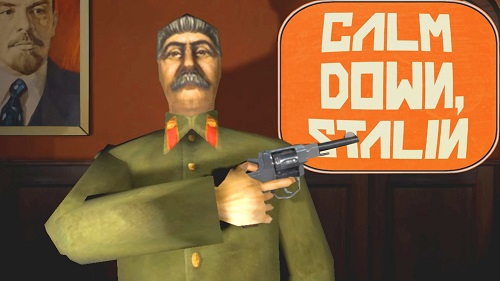

Calm Down, Stalin: Reviewed

I should not need to review a game called Calm Down, Stalin. In a just world where humans had a sense of history and understood their place as part of a much larger narrative, a game like Calm Down, Stalin wouldn’t exist. At the time of this review’s publication, 89% of the Steam reviews for Calm Down, Stalin were positive. So not only does this game exist, but its warm reception suggests we live in a world where we might soon expect to play games like Chin up, Hitler or Faffing About With Genghis Khan and Friends: A Madcap Mongolian Musical/Rape Simulator.

But let’s take a step back, if only to retreat and retrench from the inevitable cries of “artistic expression” and “freedom of speech,” and contextualize why controlling the hands of a drunk and cartoony Joseph Stalin is, at best, an exercise in historical myopia, and at worst, giving a thumbs-up to a monstrosity. An entry-level understanding of history contextualizes Stalin and the Soviet Union as one of World War II’s good guys. Are there any among us who escaped high school history without seeing Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin paling around at Yalta in February 1945?

Look at all the fun they are having.

None of the men in this picture are angels. Winston Churchill’s Battle of Britain legacy must be weighed against the German cities he ordered destroyed at the hands of the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms didn’t apply to the Japanese when he signed Executive Order 9066. Stalin, however, was different. If Churchill and Roosevelt were monsters born out of circumstance and war, then Stalin, in terms of lives lost and misery created, was the Boss Monster to end all Boss Monsters.

Stalin’s crimes against Russia and Eastern Europe are many and terrifying. Thus, I shall focus on a single aspect of Stalin’s monstrous nature as an exemplar of the whole: the Ukrainian Holodomor. The world Holodomor translates from Ukrainian as “murder by hunger.” Seven million Ukrainians, by modern estimates, starved to death in the early 1930s because of the collectivization policies Stalin instituted in 1928 as part of the first Five Year Plan. Stalin saw collectivisation as a means of ending the effective and economically viable partnership between Kulaks – land owning farmers in Ukraine – and landless farm labourers. Beginning in 1928, Kulaks were outlawed as a class and widely persecuted. Kulak assets were confiscated as state farms, and known Kulaks were either executed or exiled. At the same time, Orthodox Christianity, a bulwark of national identity and charity during times of social privation, was abolished in Ukraine in favour of Communism as a state dogma. The famine began outright when Stalin increased production quotas to unsustainable levels and further decreed that no Ukrainian farmers could eat until export quotas were met.

The manufactured famine ended in 1933, but only because Ukraine’s farmers were literally worked to exhaustion or death. Stalin’s response to this unmitigated disaster was to cover-up any evidence that it had happened. He feared the famine would lead to an international perception that the first Five Year Plan was a failure, de-legitimizing his rule and the Soviet Union in the eyes of the world. Stalin’s cover-up withstood international scrutiny until 1985.

Consider this episode from history. Try to imagine the dirty thirties as you were taught them in high school: prohibition, unemployment, Herbert Hoover and his trickle-down economics. Now imagine people in Ukraine eating rats and bugs under orders to increase production while starving to death. Now let’s talk about a game where players are tasked with controlling Stalin’s arms during the opening act of the Cold War.

The problem here isn’t one of moral outrage at using Stalin in a video game. From a historical and critical perspective, very few things should be absolutely off the table in terms of examination and deconstruction. The issue here is one of positioning and player engagement.

One might be tempted to interpret the player’s role in this game as an extended metaphor for the aides and assistants who tried to rein in Stalin’s paranoid whims. One would be wrong to do so. This isn’t a game where you control a powerless actor within a nightmare state, a la Papers, Please. Such an interpretation would recognize Stalin as the game’s antagonist. The player’s personification of Stalin, combined with the game’s action/reward system and its setting, effectively undermines any notion of the game as “Stalin Management Simulator: A Tragedy.”

Within the game, a doomsday clock looms in the background of Stalin’s office. To reverse the clock’s countdown to an “enemy invasion,” players must hover Stalin’s finger over THE BUTTON without ever pressing it. This places the game sometime between 1949, when Russia got the bomb, and 1953 – the year of Stalin’s death. During those years, Stalin’s paranoia is a matter of historical record. Managing Stalin, such that the game could be called Calm Down Stalin as an action rather than an imperative, would be fair grounds for meaningful artistic expression. Instead, nuclear brinkmanship is reduced to exploiting an enemy’s fear without ever acknowledging that “pressing the button” would escalate the Cold War and likely end the world. Sorry, developers, but a game over screen doesn’t really convey the stakes of nuclear war on either a qualitative or quantitative level.

The red telephone on Stalin’s desk, the iconic symbol of Cold War diplomacy between Kennedy/Khrushchev and later Reagan/Gorbachev, is little more than a bothersome trifle for Stalin. It is no more or less important than smoking a soothing pipe or batting at a malfunctioning lamp. The terror that should come from Stalin calling you, is nowhere to be found. Try as I might, I can’t imagine Stalin’s phone ringing off the hook, as it is depicted in the game. One simply didn’t bother the boss in this way.

Even in this, I might be content to forgive Calm Down, Stalin were it not for the way the game facilitates “managing” Stalin’s staff. As I previously mentioned, Stalin’s paranoia is a matter of record in a post-glasnost world. The deaths and deportations of the Great Purge number in the hundreds of thousands. By the late 40s and early 50s, working within Stalin’s inner circle was a decidedly high risk proposition. Calm Down, Stalin depicts this by making the player an accomplice to Stalin’s crimes.

The staff “management” challenge serves up a pistol on a silver platter. Picking up the pistol places a crosshair on the screen’s edge. Players must then make Stalin shoot an off-screen staffer in as few attempts as possible. Failure to do so damages the “state integrity” statistic. Murder, not killing, but cold-blooded murder becomes a win condition for the game. Refusing to shoot is likewise punished with a reduction to the “state integrity” statistic. What might be seen as a commentary on the casual way Stalin discarded human life is undermined by the intentional use of the Wilhelm scream when a staffer dies. Human life is reduced to comedic affectation, and thus the potential for allegory meets its own firing squad.

Marrying these executions to the notion of “state integrity” gives overt approval to Stalin’s purges as necessary to the survival of the Soviet Union. Even the likes of George Bernard Shaw, an avid Holodomor denier (that’s right, Shaw was a scumbag, and you should feel bad for going to see his plays) would be hard pressed to argue for Stalin’s purges as essential to the health of the state. To paraphrase decades of historiography, Stalin’s purges were about Stalin’s enemies, some real, many more imagined.

Thus do we come to the true danger of historical myopia. Even though I’ve never met the developers at Cardboard Games, the indie studio behind Calm Down, Stalin, not for a moment do I imagine them to be dyed-in-the-wool Stalinists. Within the artists’ hands, I do not see the feting of a monster. The ignorance at play within Calm Down, Stalin, evokes memories of teaching first-year undergraduates. By and large, they are well meaning, but they simply don’t know what they don’t know. Their sins against history are incidental rather than intentional. And in so much as I wanted to cry, “shame” while I marched these devs around King’s Landing, the prime lesson here is on the dangers that come with fostering a society that doesn’t value education in history and the liberal arts.

Calm Down, Stalin is an indecent game, but the rise of the alt-right – once again a product of historical myopia – and (shudder) Republican Presidential Candidate Donald J. Trump are all the heralds we need to recognize that we live in an indecent time. Are the developers to blame for being a product of their time? I think not. Excoriating the genuinely ignorant leads only to the production of willful ignorance. Shame ought to be reserved for the architects of a society that scoffed at the need for the liberal arts as an essential bastion of good citizenry.

Pile woe upon the culture and economy of a global West that thinks purveyors of philosophy, literature, and history are only suitable for slinging coffee. Save your slings and arrows for the teachers, “thought leaders,” and captains of business who promoted two-decades of training in “STEM” careers as the only viable path to social and economic inclusion. Calm Down, Stalin and its applause from a critical and popular audience is the first harvest of a dangerous crop. Because if we as an artistic community can so totally fail to recognize the monsters of history, what will become of us when we fail to recognize the monsters of the day?

Calm Down, Stalin: a terrible game that nobody should play.

I have my nopes since the graphics.

Everything about the game is ugly and wrong. Just wrong wrong wrong on every level. I can’t think of a single kind thing to say about it, and that has literally never happened to me before.