Adios Cowbow: Review 23 – Brain Scratch

I very nearly wrote off Brain Scratch as a failed experiment. So much of the episode’s run time is dedicated to Spike watching TV and detective work that amounts to absolutely nothing. Everything feels ephemeral as the story builds toward a deus ex machina-driven climax that is little more than a vehicle for somebody’s mom circa 1998 screeching about how video games and television will rot your brain. It feels dull and uninspired. Meta for the sake of being meta, at least right up to the last few minutes where the episode turns on a dime. That is the moment when so many of the episode’s pointless steampunk-esque cogs-on-pants reveal themselves as active gears in beautifully crafted machine.

Before I get into that, let’s talk about genre for a moment. Yes, I hear you groaning, and I don’t care. If you’ve trusted me for this long, then I’ll indulge a little bit more.

I want to ask a very serious question of this show. Does it need to be set in space? I think we can go beyond Bebop’s western inspiration and put it into the realm of fantasy. Almost none of the episodes depend on the science half of science fiction. More often than not, deus ex machina and space magic solve the stories. Allow me to illustrate the point as seen in Scratch.

Brain Scratch is about a hacker called Ronny Spangen. Ronny is also in a coma. Because this is the future, he is wired up to a dream machine that lets him create his own reality. He uses that technology, and an internet connection, to create a cult that encourages its members to upload their spirits to the internet and cast off their human bodies. Londes, the face of the cult – who is little more than a composite character that Ronny created – spouts off lines about people ridding themselves of their filthy bodies. He shuns physical needs and pleasures as the root of human misery.

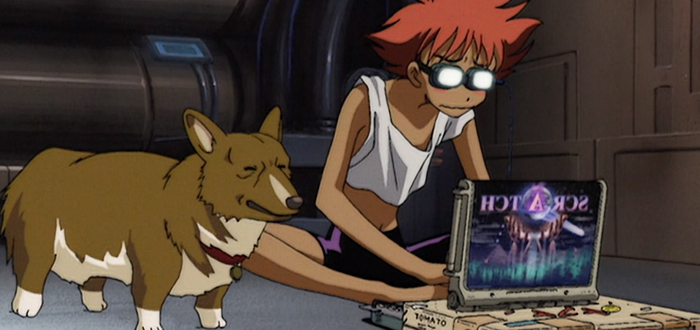

Approaching this conflict through the lens of genre, there’s nothing inherent to the story that depends on science fiction to work. Sure, Ronny is using a VR/brain controlled video game system as a method of brainwashing people into joining his cult, but the vector for this outcome could easily be transformed into a fantasy setting. To wit, Ronny is a wizard in a coma who is using his magic to try and have people join him on an isolated ethereal plane. Brainwashed villagers tell his story and only the brave paladin Sir Ein is able to meet him in psychic combat on the shrouded dreamscape. Oh yeah, that’s right, Ein not only hacks Scratch’s website, but he stops Jet from getting brainwashed. Ein is the hero of the story.

What do you say we shut it all down right here? I’m content with saying the point of Cowboy Bebop is to force us, over 23 episodes, to rethink our position on animal intelligence. The data dog saves the day, and that is the point of the show. Thank you for watching Cowboy Ein. There will be no encore.

No? Fine. I’ll continue.

All of the conflict and all of the actions in this episode easily map into a pre-industrial setting. With the exception of something like Wild Horses, that is literally an episode about nostalgia for space ships and baseball, a lot of Cowoby Bebop offers this kind of narrative flexibility.

Earlier into this review, I mentioned that much of the episode feels like ephemera and tedious world building. Only in retrospect can I appreciate Brain Scratch’s trappings as a lesson worth learning. Spike’s channel surfing through the media coverage of Scratch is deceptively generic. Masonic images and language about ascending to a higher plane could be fodder from any one of a dozen real or imagined cults. The specific language about human desire and need leading to human misery is a strategic mobilization of a few Buddhist teachings – typically the kind that show in in memes on Facebook. When Scratch’s zealots tell Spike that he won’t be able to join the church until he has his soul cleansed, it is a direct line to Scientology’s preamble. Only when Ed and Ein hack Scratch’s website, which leads them to Spange’s comatose body, do we see the cult and the world building for what it is: the manifestation of a disabled child’s pain.

All of the entry-level philosophy that Londes spouts, dialogue that evoked more than one eye-roll on my part, makes sense when the audience considers that it is coming from a petulant teenager. When Londes tells Spike that “God didn’t create man, man created God,” I was warming up to make some sort of cutting comment about somebody is getting a C- on their term paper for 2nd year philosophy class. Jet and Ed finding Ronny in a palliative care ward, however, puts all the sophomoric proselytization about television controlling people using information into its proper context. What really hit home was when Ronny realized that Ed was taking him off the network. Ronny declares, “everybody should have a body like mine.”

This single line of dialogue acts as the spine for the entire episode. Everything that happens in Brain Scratch (with the exception of Big Shot being cancelled mid-episode) is built on the actions of a person who retains a sense of self amid a fully disabled body. Ronny isn’t content to dream alone, or even have people simply visit with him. He wants to assert his will in both the physical and digital world. In making the simple pleasures of life the enemy of his cult’s philosophy, he is encouraging people to willingly give up what was taken from him. It’s pretty far afield from where the episode starts, while at the same time the outcome connects perfectly to the setup.

I feel like I should also make some mention of Brain Scratch as a disability narrative. A conscious person in a coma starting a digital cult to forge a community for himself isn’t the typical sort of ‘disability makes a person evil’ or ‘evil person is coded as evil because of their disability’ trope. Ronny/Londes is no one armed man from The Fugitive or Immortan Joe from Mad Max: Fury Road. The disability doesn’t exist to amplify the evil-nature of the character. However, Ronny wouldn’t have started a cult that led to people committing suicide if he wasn’t trapped in a body on total life support. So there is some causality in play.

However, Ronny’s story is the story of a person isolated by their injury. The security guard at the palliative care ward says that the people under their supervision have no visitors. And yet, Ronny clearly has the capacity to communicate his thoughts to the outside world despite his body. I want to believe this is commentary on how sick/injured people become social pariahs. Through that lens, Ronny is demanding nothing more than inclusion and visibility.

Even though someone might need to watch Brain Scratch twice to fully appreciate the things it does well, there’s no doubt this episode sticks the landing. The episode is also a frustrating example of how Cowboy Bebop can pivot from the bafflingly tedious, a la Cowboy Funk, to something more precise and measured. Why can’t every episode be like this? Ah well, with three episodes left, at least it seems like things are positioned to finish strong.